Recently, the emergence of cases of illness caused by the Nipah virus in India and Bangladesh has raised a global alert: could this disease, which has a fatality rate of up to 75%, trigger a new pandemic worldwide, similar to COVID-19?

Fortunately, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), the global risk potential is low, as the virus typically circulates locally in Southeast Asia. The affected countries, in fact, tend to experience nearly annual outbreaks of the disease, associated with environmental factors and local cultural practices, such as the consumption of raw date palm sap, which may be contaminated by regional bat species, natural vectors of the virus.

Brazil’s Ministry of Health has also issued a statement affirming that, given the current scenario, there is no indication of risk to the Brazilian population, although monitoring by health authorities remains ongoing. But what if the threat of a new pandemic were to originate within Brazil itself, particularly in the Amazon region, which is extraordinarily biodiverse not only in its fauna and flora, but also in its microorganisms?

According to Lívia Caricio, director of the Evandro Chagas Institute (IEC), a research institution recognized as a reference in the study of Amazonian microorganisms and their pathogenic potential, that is, their capacity to cause diseases, this is indeed a possibility, one that is increasingly associated with environmental issues such as deforestation and global warming.

INVESTIGATION

According to the director, who has a doctorate in the Biology of Infectious and Parasitic Agents, the investigation and monitoring of potentially pathogenic agents have always been at the core of the institution’s work. “This year, the institution marks its 90th anniversary. Over this period, researchers have consistently ventured into the forest to identify pathogens, whether viruses, bacteria, or fungi. Our focus has always been on addressing environmental changes and their impacts,” the researcher states.

At the time of the IEC’s founding, with the arrival of public health physician Evandro Chagas in the region, Brazil was implementing policies aimed at opening new frontiers for the exploitation of the Amazon territory, such as the “March to the West" under Getúlio Vargas’s administration and the second rubber boom, which led to the clearing of new areas of forest. In this context, endemic regional diseases such as malaria often affected those who had come to work in the region and were regarded as obstacles to its development. Established to understand the causes of these illnesses and the resulting deaths, the Institute subsequently expanded and consolidated its role.

Following its establishment, IEC researchers have consistently investigated the relationship between environmental impacts and the spread of diseases. “Whether in the construction of hydroelectric dams, mining areas, road building, or gold-mining sites, we have always worked to identify and monitor these pathogens. Today, with climate change, we have broadened this perspective even further, because it changes the patterns of certain diseases,” the director explains.

Environmental impacts shape Public Health

Lívia Caricio explains how environmental changes can contribute to rising rates of illness among the population. “When new roads are opened or large-scale projects are undertaken, preliminary studies of the area are essential to understand what will be affected, whether wildlife, vectors such as mosquitoes, or even a rich diversity of pathogens. Such projects disrupt the balance of these environments. For example, vectors that once remained within a specific area may be displaced to other regions, potentially carrying viruses, bacteria, and fungi. There may also be a spread of agents that had previously been contained within that area,” the researcher emphasizes.

Regarding global warming, the researcher notes that the spread of vector-borne pathogens, transmitted by organisms such as mosquitoes, is a growing concern. “Rising temperatures lead to greater diversity and abundance among these transmitting vectors. Some studies have already shown that warmer conditions enable the virus itself to replicate more efficiently within the vector, whether in invertebrates, vertebrates, or even humans. As a result, with more infected mosquitoes, the likelihood of transmission to new hosts increases, along with the risk of additional disease cases,” Lívia Caricio points out.

“In many cases, animals become infected with pathogens transmitted by vectors but do not fall ill, coexisting in what could be described as a form of biological balance. However, when humans enter this cycle, as new hosts with no prior exposure to the virus, they may develop the disease, potentially creating a public health concern,” the IEC director adds.

REAL RISK

According to Lívia Caricio, the potential for a new pandemic, including one originating in the Amazon, is real, given the intense global movement of people. “In the past, leaving certain regions was far more difficult. Today, a person can travel from Belém to Europe very quickly, potentially carrying pathogens. What will ultimately influence this potential is the mode of transmission,” she notes.

The researcher notes that the COVID-19 virus quickly became a pandemic due to its respiratory transmission, whereas this potential tends to be lower for diseases that rely on vectors such as mosquitoes. “Depending on the mode of transmission, a pathogen may have pandemic potential. The Zika virus, for example, was introduced in Brazil through mosquito-borne transmission. However, we later identified vertical transmission, from mother to child, as well as sexual transmission. As the virus develops additional routes of transmission, the likelihood of a higher number of cases increases,” she warns. “We can say that there is a risk that a pathogen emerging from the Amazon could cause such a scenario, and that is precisely why we conduct this monitoring, to better understand these agents,” she adds.

From forest to laboratory

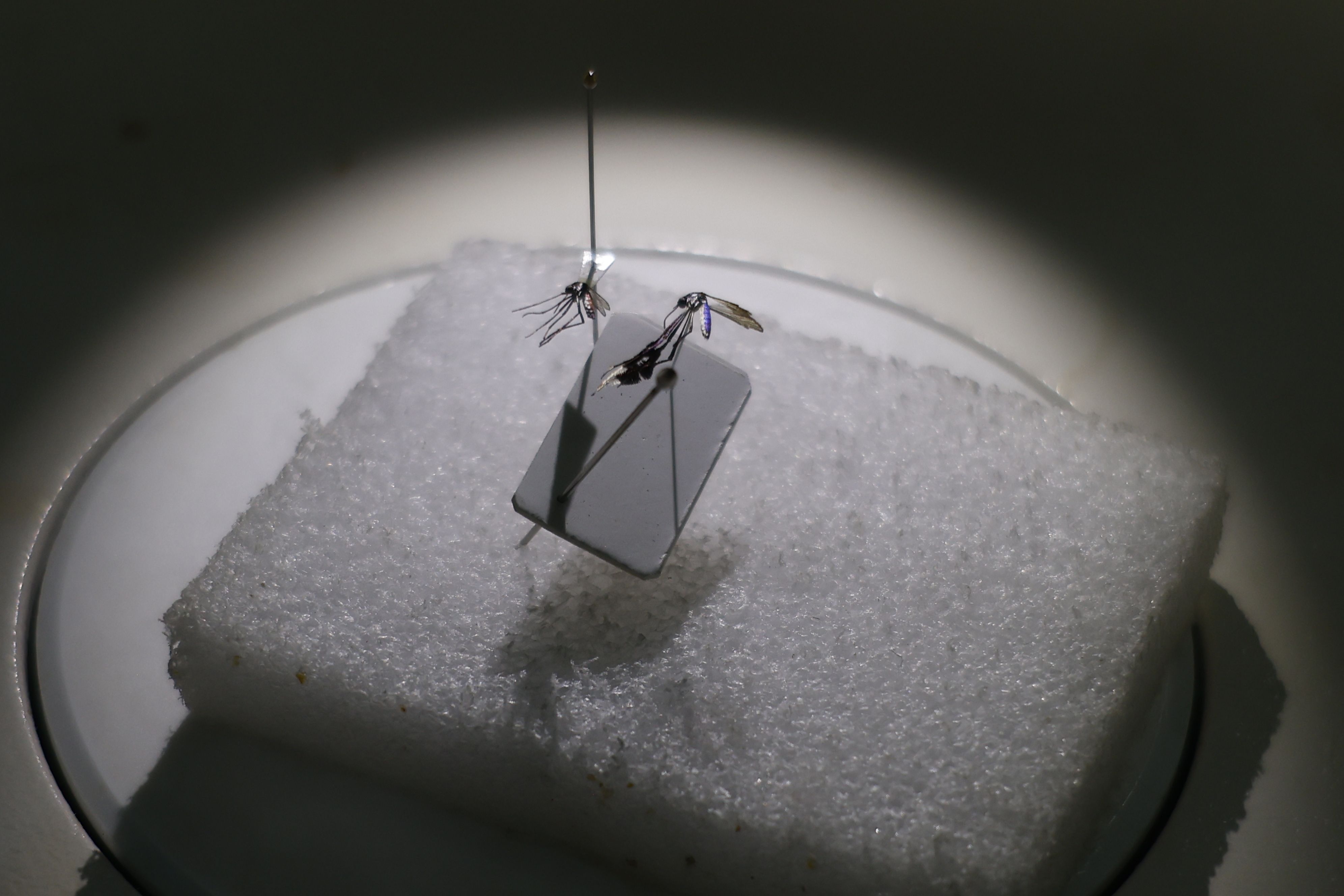

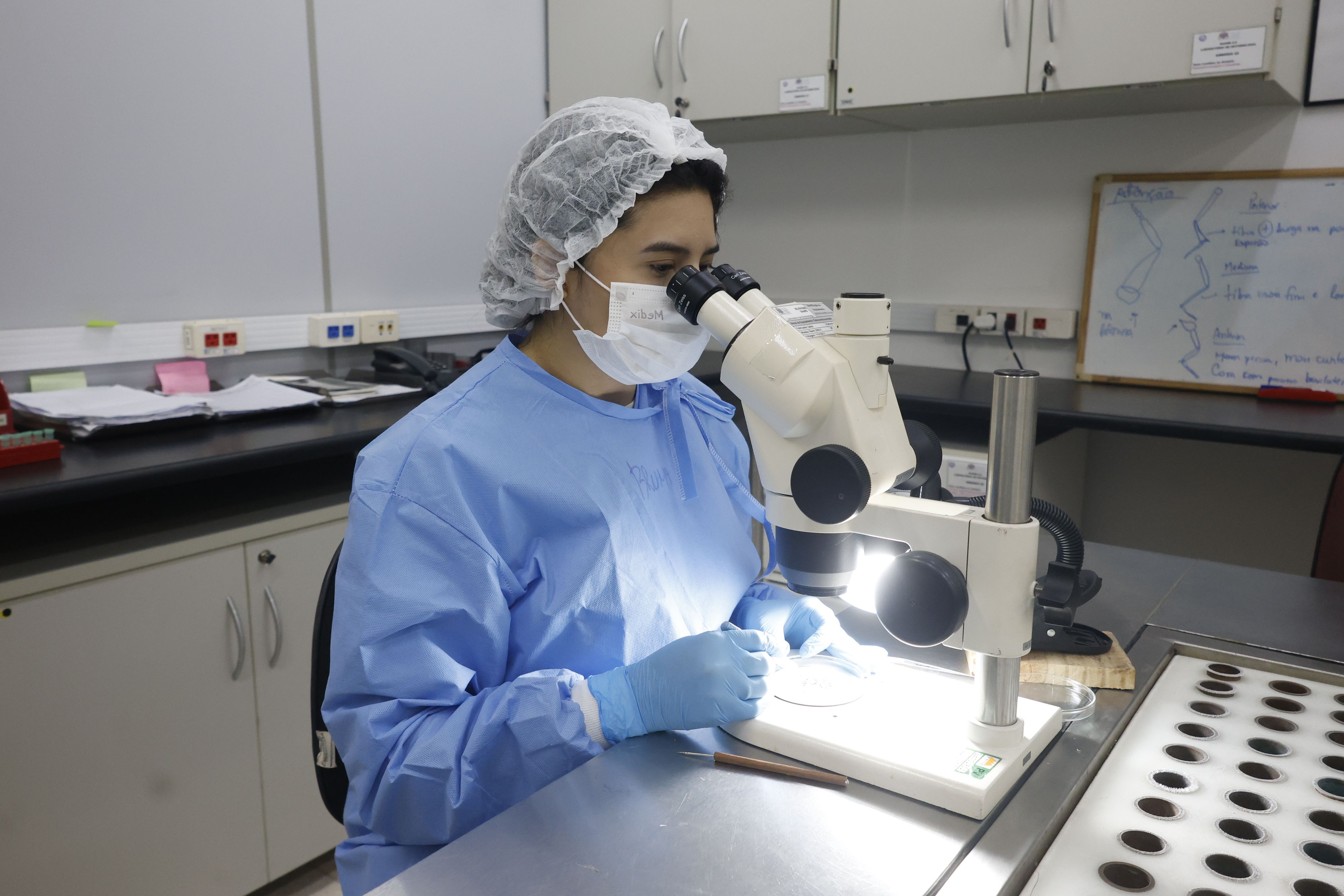

Studies conducted by the Evandro Chagas Institute begin long before the laboratory analyses carried out at the institution’s headquarters in Ananindeua, part of the Belém Metropolitan Region. They start deep within the forest. “Our teams travel into the forest to collect both vectors and wild animals that may be involved in the transmission of these pathogens, enabling us to describe the entire cycle, identify circulation patterns, isolate the microorganism, and determine its genomic sequence. Over the years, we have built a substantial repository of these agents. This allows us to detect the spread of a disease very quickly, helping to protect the population,” the director explains.

Although the Evandro Chagas Institute does not work directly on the development of vaccines or treatments for these diseases, prior knowledge of these pathogens is essential for enabling a rapid response, as demonstrated during the development of the COVID-19 vaccine. Furthermore, the Institute collaborates with other organizations in conducting clinical studies.

The Institute’s repository currently includes approximately 220 identified viruses, 36 of which are known to cause disease in humans. “Of these, 115 are new to science, meaning they have not been described anywhere else, only here in the Amazon. We have been studying their spread to other regions, as seen in the case of Oropouche fever. The virus was first isolated by the Evandro Chagas Institute because it occurred in our region, particularly in Pará. Today, it has expanded to other states in Brazil’s Northern Region, neighboring countries, and even areas beyond the Amazon,” she states.

Global warming and Chagas disease

In January, Ananindeua, part of the Greater Belém area, recorded four deaths from Chagas disease, more than had been reported over the previous five years combined. The cases were linked to oral transmission resulting from the consumption of water or food contaminated with infectious agents, possibly açaí containing triatomine bug feces. These insects transmit the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, the causative agent of the disease.

According to a study conducted by Brazilian and international universities in collaboration with the Evandro Chagas Institute, global warming may facilitate the spread of triatomine bugs, potentially increasing the number of Chagas disease cases. The research projected scenarios through 2080 and identified a trend suggesting that these insects may expand across the Amazon, not only in areas already known to be vulnerable but also into regions currently considered safe from Chagas disease that could become more susceptible to transmission in the future. Climate change is expected to be the primary driver of this spread. Such projections allow health systems to anticipate and better plan their response strategies.

ADAPTATION

“The World Health Organization (WHO), the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), and numerous countries committed to eliminating certain diseases by 2030, including Chagas disease, malaria, and others. But with 2030 fast approaching, instead of achieving elimination, projections now indicate an increase. As a result, the focus is no longer on elimination but on reducing the number of cases, as we are confronting the consequences of environmental change,” the IEC director states.

According to her, this is precisely why the 30th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30), held in Belém, has shifted the discussion from mitigation to adaptation. “The key question is how health systems must be structured, given what we know: case numbers will rise, and new diseases will emerge. That is what we have been preparing for,” she concludes.

INSTITUTIONAL PARTNERSHIP

The production of Liberal Amazon is one of the initiatives of the Technical Cooperation Agreement between the Liberal Group and the Federal University of Pará. The articles involving research from UFPA are revised by professionals from the academy. The translation of the content is also provided by the agreement, through the research project ET-Multi: Translation Studies: multifaces and multisemiotics.